The Assemblage You Call Yourself: Rethinking Creative Identity at Year's End

What quantum physics, French philosophy, and Jewish mysticism reveal about how creativity actually works

It’s late December, and I’m doing what every creator does this time of year: taking a hard look at what I did, what I didn’t do, what worked, and what I need to get better at.

This process got me inspired to get a bit more theoretical here, and perhaps more inspiring too. I’m sure you are aware of my broad understanding that all creation is relational, but I think I never introduced you to the theoretical framework that has been my guiding principle for more than 10 years now: relational ontologies.

The Ontological Shift That Changes Everything

We’ve built an entire culture on a foundational misunderstanding about what things are.

We think the world is made of distinct, bounded entities that occasionally interact. You’re a separate person. I’m a separate person. We meet, we talk, we influence each other, but we remain fundamentally independent.

This seems obvious and self-evident, but what if it’s completely wrong?

Relational ontology is a philosophical framework that challenges this point of view. Ontology is the study of what exists, the nature of being itself, and relational ontology proposed a different perspective: nothing exists independently. Everything that exists does so only through relation.

You’re not a thing that then relates to other things. You ARE your relations. Strip away every connection, every influence, every interaction, and there’s no “you” left over. Relations don’t happen to pre-existing entities. Relations constitute entities.

This isn’t a metaphor about interconnectedness or some vague spiritual idea about oneness. It’s a fundamental rethinking of what existence means. And once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

Karen Barad and the Physics of Becoming

Karen Barad came to this realization from an unexpected place: quantum physics.

Barad is a theoretical physicist who got obsessed with a problem at the heart of quantum mechanics. When you study subatomic particles, you are forced to deal with the strange fact that they don’t have definite properties until they’re measured. An electron doesn’t have a specific position or momentum floating around in space, waiting to be discovered. It exists in a state of indeterminacy until something interacts with it.

Most physicists treat this as a measurement problem, a quirk of observation, but Barad saw something more profound and, to me, much more relevant. What if this wasn’t about measurement at all? What if it revealed the fundamental nature of reality?

She developed what she calls “agential realism,” and the core insight is that entities don’t pre-exist their interactions. They emerge through what she calls “intra-action.”

Notice that word. Not interaction (which implies two separate things coming together) but intra-action. The very act of relating is what brings distinct entities into being.

Barad writes: “We are not independent entities. We are relations all the way down.” There is no fixed “you” that then enters into relationships. You are continuously being created through your entanglements with the world.

Think about what this means for creativity. You’re not a creator who possesses ideas that you then share with the world. You and your ideas and your audience are mutually constituted through the creative act itself.

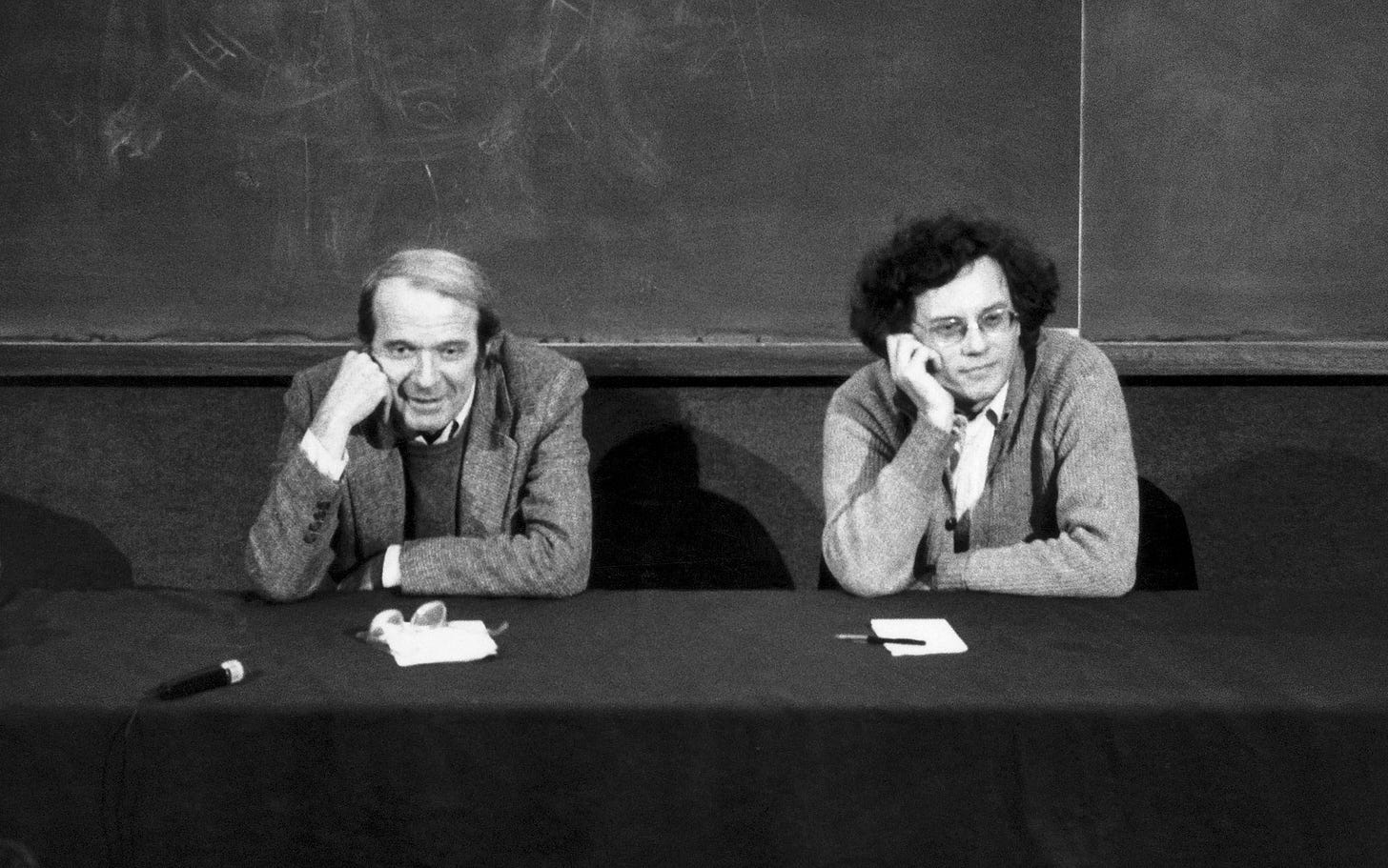

Deleuze and Guattari: The Rhizome of Creativity

While Barad came from physics, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari arrived at similar conclusions from philosophy and psychoanalysis.

They rejected what they called “arborescent thinking”, which is the tree model where everything branches from a single root, a single origin. Our western culture loves this model. We want to trace ideas back to their source, find the original genius, identify the primary cause.

But Deleuze and Guattari said reality works more like a rhizome, like grass or ginger root that spreads horizontally in all directions with no central point, no hierarchy. Any point can connect to any other point. There are no origins, only middles.

They write: “A rhizome has no beginning or end; it is always in the middle, between things, interbeing, intermezzo.”

For them, you’re not a stable identity that creates. You’re what they call an “assemblage”, which is a temporary configuration of flows, desires, materials, and forces. Your creativity doesn’t emerge from your essential self because there is no essential self. There are only assemblages that form, transform, and dissolve.

Think about your creative process. Where does an idea actually start? You might say “I had an idea in the shower,” but where did that come from? Something you read combined with something you overheard combined with a problem you’ve been working on combined with the particular biochemical state of your brain in that moment combined with the warm water and the slight boredom. It’s not a linear chain of causation, it’s a rhizome, with multiple flows intersecting to produce something new.

Deleuze and Guattari also say you should multiply these connections instead of protecting them. The goal isn’t to develop a pure, independent voice, it’s to become a productive site of intersection. Let more flows pass through you. Create more assemblages. Steal, combine, remix. Your creativity is richer the more promiscuous your connections.

They call this “deterritorialization”, or breaking down the boundaries that separate you from others, that make you think your ideas are really “yours.” The most creative moments happen when you allow yourself to be deterritorialized, when the borders dissolve and new assemblages can form.

Martin Buber and the Space Between

There’s a third voice I want to bring in here, someone who approached relational ontology from a completely different angle: Martin Buber, the Jewish philosopher and theologian.

Buber’s most famous work is a slim book called “I and Thou,” and in it, he makes a distinction that cuts to the heart of how we relate to the world.

He says we live in two modes. The “I-It” mode treats everything, including people, as objects to be used, analyzed, categorized. This is the mode of control and consumption. The “I-Thou” mode is different, it’s when we encounter something or someone as a living presence, not as an object for our purposes but as a genuine other we’re in dialogue with.

In the I-Thou relation, Buber says, there is no “I” without the “Thou.” The self doesn’t exist prior to relation. “In the beginning is relation,” he writes. Not two separate beings who then relate, but relation itself as the primary reality from which distinct beings emerge.

Buber says this applies to creative work too. When you’re truly creating, you’re in an I-Thou relationship with your materials, your subject, even your emerging work itself. You’re not imposing your will on passive materials, you’re in dialogue. The painting talks back. The essay resists. The melody suggests where it wants to go.

The work becomes through the relation, and so do you.

Buber writes: “All real living is meeting.” Not thinking, not producing, not achieving - meeting. The creative act is fundamentally relational, a meeting between you and something other, and both of you are changed in the encounter.

What This Means for How You See Your Year

Okay, so three different thinkers, three different angles, but they’re all circling the same profound realization: you don’t exist as a bounded, independent entity. You’re a node in a network, an assemblage of flows, a relational event.

And if that’s true, then your year-end inventory needs to completely change.

The usual questions we ask, like “What did I accomplish? What did I produce? How much did I grow?” all assume a stable “I” that does things and possesses qualities. But from a relational ontology perspective, those aren’t even the right questions.

Better questions might be:

What relations constituted my creative work this year?

What assemblages formed that allowed new work to emerge?

What intra-actions changed both me and my work?

Where did I meet the world in genuine I-Thou encounters?

What flows passed through me and created something neither I nor they could have produced alone?

Mapping our year this way makes everything look different.

So here is an exercise for you: pick one thing you made this year that feels significant, and instead of celebrating it as “your” achievement, try to map the assemblage that produced it.

Start with the obvious relations: Who influenced this? What books or art fed into it? Who gave feedback? Who shared it?

But then go deeper. What constraints shaped it? What technical limitations forced you to be creative? What platform affordances influenced its form? What failures or rejections led you here? What was happening in your life that created the emotional substrate for this work?

Go deeper still. What flows of capital made this possible? What historical lineages of ideas does it draw from? What language patterns and cultural references structure it in ways you don’t even notice?

If you really trace it, you’ll find that this thing you made has no clear boundary. It bleeds out in all directions, connected to everything.

Deleuze and Guattari would say you’ve mapped a rhizome. Barad would say you’ve traced the intra-actions that brought this work into being. Buber would say you’ve recognized the meetings that constituted it.

The Freedom in Losing Yourself

There’s this moment of vertigo when you first really grasp relational ontology. If I’m not a bounded, independent self, then who am I? If my work isn’t really “mine,” then what’s the point?

But the vertigo passes, and what’s on the other side is actually freedom.

You don’t have to be a genius. The weight of isolated creativity lifts. You don’t have to generate everything from nothing because nothing comes from nothing. Everything emerges from relation.

You don’t have to protect your ideas as precious possessions because they were never yours alone. They were always assemblages, always rhizomatic, always co-created.

You don’t have to be perfect because there’s no stable “you” to perfect. You’re always becoming through your relations, which means you can always become differently by seeking different relations.

This changes the entire strategy for creative work.

The old model says: develop your unique voice, protect your intellectual property, build your personal brand, differentiate yourself from competitors.

The relational model says: multiply your connections, be promiscuous with influences, collaborate generously, become a productive node in creative networks.

The old model is about fortress-building. The relational model is about bridge-building.

Looking Ahead: The Relations You’ll Seek

So as this year ends, I’m not asking myself “What will I accomplish next year?”

I’m asking: “What relations will I seek? What assemblages will I help form? What flows will I allow to pass through me? What genuine meetings will I create space for?”

I’m thinking about this practically:

Multiply your inputs: Read outside your field, talk to people who think differently, seek art that confuses you. Let more flows intersect in you, and don’t worry too much about maintaining a “coherent” brand or vision. Coherence is overrated, and assemblages are productive precisely because they’re heterogeneous.

Make your collaborations visible: Stop pretending you did it alone and credit your influences. Share your process, including all the ways others shaped it.

Seek genuine meetings: Buber’s I-Thou relation can’t be forced, but you can create conditions for it. Slow down, pay attention, approach your materials, your collaborators, even your audience as living presences you’re in dialogue with, not objects for your use.

Build for entanglement, not independence: Structure your creative practice to maximize productive relations. Join communities, start accountability partnerships, collaborate on projects, share half-formed ideas, and let your work be changed by others.

Track assemblages, not accomplishments: Keep a journal not of what you did, but of what relations you participated in. What meetings happened? What flows intersected? What intra-actions occurred?

The Year Ahead Is Already Relational

What Barad, Deleuze and Guattari, and Buber (and me) all understand is that the relational nature of reality isn’t something you opt into, it’s what’s already happening, whether you acknowledge it or not.

The only question is whether you’ll work with this reality or against it.

Your best work next year won’t come from digging deeper into isolation. It’ll come from seeking richer relations, forming stranger assemblages, allowing more transformative meetings.

And that’s not a limitation. That’s where all the possibility lives.

All creation is relational. If you found this post helpful, please consider sharing it with other creators or supporting me with a one-time contribution. ♡

A quote to inspire:

“There is no fixed subject unless there is repression.”

— Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari

This is very thought provoking! I was just feeling somewhat isolated in my creativity, worried that making more art would mean spending more time alone.

But I'm definitely going to try the mapping exercise to see how even if I spend time producing things without other people there, I'm still being influenced by relations that accumulated along the way to that moment.

I think a lot about the 80-year-old neighbor lady who taught me to crochet when I was 8 years old. That relationship is still going strong even though I haven't spoken to her physically in decades.

What is a "platform affordance"?